[SIGIR-24] SelfGNN: Self-Supervised Graph Neural Networks for Sequential Recommendation

1. Problem Definition

In Liu et. al (2024) they propose a self-supervised method for modeling long and short-term interaction sequences for user-item recommendation. They call this method Self-Supervised Graph Neural Network (SelfGNN) which they analize with the following research questions (RQ):

- How does SelfGNN perform w.r.t top-k recommendation as compared with the state-of-the-art models?

- What are the benefits of the components proposed?

- How does SelfGNN perform in the data noise issues?

- How do the key hyperparameters influence SelfGNN?

- In real cases, how can the designed self-augmented learning in SelfGNN provide useful interpretations?

2. Motivation

As stated by the paper (Liu et. al) recommender systems are an important field of research for addressing user-item interactions benefitting service providers such as Amazon (Ge et al. 2020) but also digital platforms such as TikTok, YouTube and Facebook (Wei et al. 2023; Zhang et al. 2021). Furthermore, self-supervised learning (SSL) have become very attractive for recommender systems and graph learning as they additional graphical structure compensates for the lack of labelled data. SSL methods are only limited to a few labeled data points thus enabling usages for many more applications.

An important branch of recommender systems is sequential recommendation, which models user interactions over time (as a sequence of actions in time). Thus, by analyzing the temporal interaction patterns the model can predict future user actions. Examples of sequential recommendation could be the task of predicting the next movie a user wants to watch given the ordered list of previously watched movies (as presented in the lectures). Modeling sequential patterns can be crucial recommender systems as they relay chronological patterns giving insights into both short and long-term user preferences (Liu et al.). Thus many studies have analyzed how to incorporate temporal information to the recommender system such as DGSR (Zhang et al. 2023), SURGE (Chang et al. 2021), GRU4Rec (Hidasi et al. 2016), SASRec (Kang and McAuley 2018), Bert4Rec (Liu et al. 2019), TiSASRec (Li et al. 2020) and MBHT~\cite{MBHT} (where the last four methods are based on Transformers (Vaswani et al. 2017)). However, while these models manage to model dynamic user-interactions they fail to effectivly integrate both long and short-term interaction or overlook important periodical collaborative relationships between users by only encoding single-user sequences (Liu et al. 2024). Furthermore, previous SSL methods for sequential recommendation like CLSR~\cite{CLSR}, are extremely dependent on high-quality data. This means they lack the natural robustness to noisy data which is present in real-world data as the noise will propagate through the model (Lie et al. 2024).

With these issues in mind, SelfGNN was designed to effectively encode both long and short-term interaction while denoising the short-term patterns with long-term dependencies thus making the model robust to noisy data (Liu et al. 2024).

3. Preliminary

3.1 Message Passing

Message Passing is the central process of Graph Convolution Networks (GCN) to encode graph information such as nodes~\cite{Kipf}. The core idea is to send messages of information between the nodes to iteratively update the encoded node representations~\cite{Kipf}. In this paper (Lie et al. 2024) were inspired by LightGCN~\cite{LightGCN} where each user-node $\boldsymbol{e}_ {u}^{(k)}$ and item-node $\boldsymbol{e}_ {i}^{(k)}$ encoding are updated by the weighted sum of their neighboring nodes:

$ \boldsymbol{e}_ {u}^{(k+1)} = \sum_ {i\in\mathcal{N}_ u} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\vert\mathcal{N}_ u\vert}\sqrt{\vert\mathcal{N}_ i\vert}}\boldsymbol{e}_ {i}^{(k)} $

$ \boldsymbol{e}_ {i}^{(k+1)} = \sum_ {u\in\mathcal{N}_ i} \frac{1}{\sqrt{\vert\mathcal{N}_ i\vert}\sqrt{\vert\mathcal{N}_ u\vert}}\boldsymbol{e}_ {u}^{(k)} $

Where $\boldsymbol{e}_ {u}^{(0)}$ and $\boldsymbol{e}_ {u}^{(0)}$ are the inital ID embedding for the user and item respectivly.

3.2 Self-Attention

Another key operation for propagating information which has seen increased popularity for graph-based learning is self-attention (Vaswani et al. 2017). The idea of self-attention is to project the input $\boldsymbol{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times d}$ to the query, key and value subspace using (the learned) projection matrices $\boldsymbol{W}_ Q\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d_ Q}$, $\boldsymbol{W}_ K\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d_ K}$, and $\boldsymbol{W}_ V\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d_ V}$, respectivly (where $d_ K = d_ Q$). Then (single-head) attention is computed by:

$ \text{Attn}(\boldsymbol{X}) = \text{Softmax}\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{XW}_ {Q}(\boldsymbol{XW}_ K)^\mathsf{T}}{\sqrt{d_ K}}\right)\boldsymbol{XW}_ V = \text{Softmax}\left(\frac{\boldsymbol{QK}^\mathsf{T}}{\sqrt{d_ K}}\right)\boldsymbol{V} $

3.3 Validation Metrics

To validate the effectiveness of their proposed method, (Liu et al. 2024) use the Hit Rate (HR)@N and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG)@N (www.evidentlyai.com). To calculate the Hit Rate for top $N$ recommendations, each user gets a score of either 0 or 1 depending on if they were recommended a relevant item in their top $N$ recommendations. Then we calculate the average score for all users, which is the final validation metric.

To calculate the Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain, we first calculate the Discounted Cumulative Gain (DCG) and then normalize it using the Idealized discounted cumulative gain (IDCG) (www.evidentlyai.com). For a user with predicted item ranking-position order $p_ i$ and ground-truth item-relevance $r_ i$ DCG@N is computed as:

$ DCG@N = \sum_ {i = 1}^N \frac{r_ i}{\log (p_ {i} +1)} $

The idea of NDCG is to normalize the DCG with the ideal discounted cumulative gain (IDCG). The equation for IDCG is almost equivalent to that of DCG, however, we just assume that the item positions $p_ i$ are ordered according to their relevance $r_ i$. This way, the IDCG represents the best possible ranking order the recommender could produce. With this in mind, the final equation for NDCG is:

$ NDCG@N = \frac{DCG@N}{IDCG@N} = \frac{\sum_ {i = 1}^N \frac{r_ i}{\log (p_ i +1)}}{\sum_ {i = 1}^N \frac{r_ i}{\log (p’_ {i} +1)}} \in [0,1] $

In the paper by Liu et al. they set $N = {10,20}$ for both HR@N and NDCG@N.

4. Method

Given the set of users $\mathcal{U} = {u_ 1,\dots, u_ I}$ with $\vert\mathcal{U}\vert = I$ and the set of items $\mathcal{V} = {v_ i,\dots,v_ J}$ where $\vert\mathcal{V}\vert = J$ the time-dependent adjacency matrix $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}_ {t} \in\mathbb{R}^{I\times J}$ represents the user-item interaction at time $t$. Here, the time $t$ is discretized by the hyperparameter $T$ such that each time-interval has length $(t_ e - t_ b)/T$ where $t_ b$ and $t_ e$ is the first (beginning) and last (end) observed time stamp. Thus in other words, ${\mathcal{A}}_ {t,i,j}$ is set to 1 if user $u_ i$ interacted with item $v_ j$ at time $t$. Then giving ${\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}_ {t}| 1\leq t \leq T}$ the objective is to predict future user-item interactions $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}_{T+1}}$. Formally, they define the objective as:

$ \arg\min_ {\Theta_ f,\Theta_ g} \mathcal{L}_ {recom}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{\hat{A}}_ {T+1}},\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}_ {T+1}}\right) + \mathcal{L}_ {SSL}(\boldsymbol{E}_ s,\boldsymbol{E}_ l) $

$ \boldsymbol{\mathcal{\hat{A}}_ {T+1}} = f\left(\boldsymbol{E}_ s,\boldsymbol{E}_ l\right)\quad \boldsymbol{E}_ s,\boldsymbol{E}_ l = g({\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}_t}) $

Where $\mathcal{L}_ {recom}$ is the recommendation error between the true and predicted user-item interactions $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}_ {T+1}}$ and $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{\hat{A}}_ {T+1}}$, respectively. $\mathcal{L}_ {att}$ is the self-attention loss (regularizer) which uses the long and short-term embeddings $\boldsymbol{E}_ l,\boldsymbol{E}_ s$ which are encoded using the sequential data and encoder $g$. Lastly, the estimated predictions $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{\hat{A}}_ {T+1}}$ is also calculated using these embeddings and prediction function $f$.

4.1 Encoding Short-term user-item interactions

The model begins by modeling the short-term interactions as these will be used throughout the whole encoding process. Inspired by LightGCN~\cite{LightGCN}, they project each user $u_ i$ and item $v_ j$ for each timestep $t$ into a $d$-dimensional latent space (using the ID). These embeddings $\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i}^{(u)}$, $\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j}^{(v)}$ are assembled to the embedding matrices $\boldsymbol{E}_ t^{(u)}\in\mathbb{R}^{I\times d}$,$\boldsymbol{E}_ t^{(v)} \in\mathbb{R}^{J\times d}$ which are then updated through the following message passing method:

$ \boldsymbol{z}_ {t,i}^{(u)} = \text{LeakyReLU} \left( \mathcal{A}_ {ti,{*}} \cdot \boldsymbol{E}_ t^{(v)}\right), \quad \boldsymbol{z}_ {t,j}^{(v)} = \text{LeakyReLU} \left( \mathcal{A}_ {tj,{*}} \cdot \boldsymbol{E}_ t^{(u)} \right) $

This is repeated for $L$-layers with the embeddings in the $l$-th layer defined as:

$ \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,l}^{(u)} = \boldsymbol{z}_ {t,i,l}^{(u)}+\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,l-1}^{(u)},\quad \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,l}^{(v)} = \boldsymbol{z}_ {t,i,l}^{(v)}+\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,l-1}^{(v)} $

Finally, all embeddings for each layer are concatenated together to form the final short-term embeddings $\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i}^{(u)}$ and $\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j}^{(v)}$:

$ \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i}^{(u)} = \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,1}^{(u)}| \dots| \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i,L}^{(u)},\quad\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j}^{(v)} = \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j,1}^{(v)}| \dots| \boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j,L}^{(v)} $

4.2 Encoding Long-term user-item interactions

The long-term user-item information is encoded in two different ways which in the end are combined for the final prediction. First, we have what they call Interval-Level Sequential Pattern Modeling which aims to capture dynamic changes from period to period by integrating the aforementioned short-term embeddings into long-term embeddings using temporal attention. Second, the use Instance-Level Sequential Pattern Modeling which aims to learn the pairwise relations between specific item instances directly (Liu et al. 2024).

Interval-Level Sequential Pattern Modeling To integrate short-term embeddings into long-term ones Liu et al. (2024) use the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) on the sequential short-term embeddings ${\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i}^{(u)}}$ and ${\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j}^{(v)}}$ for each user $u_ i$ and item $v_ j$. More specifically, each hidden state $\boldsymbol{h}_ {t,i}^{(u)}$ and $\boldsymbol{h}_ {t,j}^{(v)}$ of the GRU model is collected to interval-level sequences $S_ i^{interval}$ and $S_ j^{interval}$:

$ S_ i^{interval} = \left(\boldsymbol{h}_ {1,i}^{(u)},\dots,\boldsymbol{h}_ {T,i}^{(u)}\right),\quad S_ j^{interval} = \left(\boldsymbol{h}_ {1,j}^{(v)},\dots,\boldsymbol{h}_ {T,j}^{(v)}\right) $

where:

$ \boldsymbol{h}_ {t,i}^{(u)} = \text{GRU}\left(\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,i}^{(u)},\boldsymbol{h}_ {t-1,i}^{(u)}\right) ,\quad \boldsymbol{h}_ {t,j}^{(v)} = \text{GRU}\left(\boldsymbol{e}_ {t,j}^{(v)},\boldsymbol{h}_ {t-1,j}^{(v)}\right) $

Then (multi-head dot-product) self-attention (Vaswani et al. 2017) is applied for the interval-level sequences to uncover the temporal patterns:

$ \boldsymbol{\bar H}_ i^{(u)} = \text{Self-Att}\left(S_ i^{interval} \right),\quad \boldsymbol{\bar H}_ j^{(v)} = \text{Self-Att}\left(S_ j^{interval} \right), $ Which finally, are summed across time:

$ \boldsymbol{\bar e}_ i^{(u)} = \sum_ {t=1}^T \boldsymbol{\bar H}_ {i,t}^{(u)},\quad \boldsymbol{\bar e}_ j^{(v)} = \sum_ {t=1}^T \boldsymbol{\bar H}_ {j,t}^{(v)} $

Where $\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ i,\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ j\in\mathbb{R}^{d}$ is final the long-term (interval-level) embeddings for user $u_ i$ and item $v_ j$. Note, that while the short-term embeddings are dependent on the given time-interval $t$ the long-term embeddings are independent of $t$ as while the long-term as $t$ is effectively integrated out.

Instance-Level Sequential Pattern Modeling However, interval-level embeddings are not the only long-term embeddings used in the SelfGNN. The model also uses instance-level sequential patterns by applying self-attention directly over sequences containing users’ interacted item instances (Liu et al. 2024). Given a user $u_ i$ they denote the $m$’th interacted item for set user as $v_ {i,m}$ for $m = {1,\dots,M}$ (for a set maximum interaction length $M$). Then the sequences of items user $u_ i$ interacted with can be modeled as:

$ S_ {i,0}^{instance} = \left(\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ {v_ {i,1}}^{(v)}+ \boldsymbol{p}_ 1,\dots,\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ {v_ {i,M}}^{(v)} + \boldsymbol{p}_ M\right) $

Where $\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ {v_ {i,m}}^{(v)} \in\mathbb{R}^d$ is the aforementioned long-term embedding for item $v_ {i,m}$ and $\boldsymbol{p}_ m\in\mathbb{R}^d$ is learnable position embeddings for the $m$-th position. Then $L_ {attn}$ layers of self-attention (with residual connections) are applied on the instance-level sequence $S_ {i,0}^{instance}$:

$ S_ {i,l}^{instance} = \text{LeakyReLU}\left(\text{Self-Attn}\left(S_ {i,l-1}^{instance}\right)\right) + S_ {i,l-1}^{instance} $

The final instance-level embedding is calculated by summing over the elements of the final sequence $S_ {i,L_ {attn}}^{instance}$:

$ \boldsymbol{\tilde e}_ i^{(u)} = \sum S_ {i,L_ {attn}}^{instance} $

Predicting Future user-item interactions The prediction for new user-item interactions $\mathcal{\hat A}_ {T+1,i,j}$ for user $u_ i$ and item $v_ j$ is now computed using the long-term embeddings (which implicitly uses the short-term embeddings):

$ \mathcal{\hat A}_ {T+1,i,j} = \left(\boldsymbol{\bar e}_ i^{(u)} + \boldsymbol{\tilde e}_ i^{(u)} \right)^{\mathsf{T}} \cdot \boldsymbol{\bar e}_ j^{(v)} $

They optimize with the following loss function (to prevent predicted values from becoming arbitrarily large):

$ \mathcal{L}_ {recom} \left(\mathcal{A}_ {T+1,i,j},\mathcal{\hat A}_ {T+1,i,j}\right) = \sum_ {i = 1}^I \sum_ {k=1}^{N_ {pr}} \max \left(0,1 -\mathcal{\hat A}_ {T+1,i,p_ {k}} + \mathcal{\hat A}_ {T+1,i,n_ k} \right) $

where $N_ {pr}$ is the number of samples and $p_ k$ and $n_ k$ is the $k$-th positive (user-interaction) and negative (no user-interaction) item index respectively.

4.3 Denoising short-term user-item interactions

While short-term user interactions are important for modeling sequential user-item interaction patterns they often contain noisy data. Here noise refers to any temporary intents or misclicks, which cannot be considered as long-term user interests or new recent points of interest for predictions (Liu et al. 2024). An example of this is when an Aunt buys Modern Warfare III for their nephew for Christmas as this interaction does not reflect user $u_ {Aunt}$’s interests. Other examples are simple misclicks or situations where you click on something expecting it to be a different thing. Thus to denoise these noisy short-term user-item interactions Liu et al. (2024) propose to use filter them using long-term interactions. Specifically, for each training sample of the denoising SSL, they sample two observed user-item edges $(u_ i,v_ j)$ and $(u_ {i’},v_ {j’})$ from the short-term graphs $\boldsymbol{\mathcal{A}}_ {t}$ and calculate the likelihood $s_ {t,i,j}, \bar{s}_ {i,j},s_ {t,i’,j’}, \bar{s}_ {i’,j’} \in\mathbb{R}$ that user $u_ i$/$u_ {i’}$ interacts with item $v_ j$/$v _ {j’}$ at time-step $t$ and in the long-term, respectively. For $(u_ i,v_ j)$ the likelihoods are ($s_ {t,i’,j’}, \bar{s}_ {i’,j’}$ are calculated in the same way):

$ s_ {t,i,j} = \sum_ {k= 1}^d \text{LeakyReLU}\left(e_ {t,i,k}^{(u)}\cdot e_ {t,j,k}^{(v)}\right),\quad \bar{s}_ {t,i,j} = \sum_ {k= 1}^d \text{LeakyReLU}\left(\bar{e}_ {i,k}^{(u)}\cdot \bar{e}_ {t,j,k}^{(v)}\right) $

Where $e_ {t,i,k}^{(u)},e_ {t,j,k}^{(v)},\bar{e}_ {i,k}^{(u)},\bar{e}_ {t,j,k}^{(v)}\in\mathbb{R}$ is the element value of the $k$-th embedding dimension. Thus the SSL objective functions become:

$ \mathcal{L}_ {SSL} = \sum_ {t=1}^T\sum_ {(u_ {i},v_ {j}),(u_ {i’},v_ {j’})} \max\left(0,1- (w_ {t,i}\bar{s}_ {t,i,j} - w_ {t,i’}\bar{s}_ {t,i’,j’})\cdot (s_ {t,i,j} -s_ {t,i’,j’} )\right) $

With learnable stabilty weigths $w_ {t,i’},w_ {t,i’}\in\mathbb{R}$ calculated using the short and long-term embeddings:

$ w_ {t,i} = \text{Sigmoid}\left(\boldsymbol{\Gamma}_ {t,i} \cdot\boldsymbol{W}_2 + b_2\right) $

$ \boldsymbol{\Gamma}_ {t,i} = \text{LeakyReLU} \left( \left( \boldsymbol{\bar{e}}^{(u)}_ {i} + \boldsymbol{e}^{(u)}_ {t,i} + \boldsymbol{\bar{e}}^{(u)}_ {i} \odot \boldsymbol{e}^{(u)}_ {t,i} \right) \boldsymbol{W}_ {1} + \boldsymbol{b}_ {1} \right) $

With learnable parameters $\boldsymbol{W}_ {1}\in\mathbb{R}^{d\times d_ {SSL}}$, $\boldsymbol{W}_ {2}\in\mathbb{R}^{d_ {SSL}\times 1}$, $\boldsymbol{b}_ {1}\in\mathbb{R}^{d_ {SSL}}$, and ${b}_ {2}\in\mathbb{R}$. Thus the final learning objective becomes:

$ \mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_ {recom} + \lambda_ {1}\mathcal{L}_ {SSL} + \lambda_ {2}\cdot \vert \Theta\vert _ F^2 $

For weight-importance parameters $\lambda_1$ and $\lambda_2$. The complete procedure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Overview of the SelfGNN framework

5. Experiment

5.1 Experiment setup

As mentioned in the beginning, the following experiments are designed to answer the aforementioned research questions.

Data sets The SelfGNN model is tested using an Amazon-book dataset (user ratings of Amazon books) (He and McAuley 2016), Gowalla dataset (user geolocation check-ins) (Cho et al. 2011), Movielens dataset (users’ ratings for movies from 2002 to 2009)(Harper and Konstant 2015), and Yelp data set (venue reviews sampled from 2009 to 2019) (Liu et al. 2024). Furthermore the 5-core setting is applied which removes all users and items with less than 5 interactions.

Baselines They test their method against a plethora of methods. This includes BiasMF (Koren et al. 2009), NCF (He et al. 2017), GRU4Rec (Hidasi et al. 2016), SASRec (Kang and McAuley 2018), TiSASRec (Li et al. 2020), Bert4Rec (Liu et al. 2019), NGCF (Wang et al. 2019), LightGCN~\cite{}, SRGNN~\cite{}, GCE-GNN~\cite{}, SURGE (Chang et al. 2021), ICLRec~\cite{}, CoSeRec~\cite{}, CoTRec~\cite{}, and CLSR~\cite{}.

Evaluation For evaluation the data sets were split by time such that the most recent observations were used for testing, the earliest observations were used for training, and the remaining (middle) observations were used for validation. Furthermore, 10.000 users were sampled as test users for which negative samples were sampled by selecting 999 items the test user had not interacted with. Lastly, they use Hit rate (HR)@N and Normalized Discounted Cumulative Gain (NDCG)@N for $N = {10,20}$ as their evaluation metrics.

5.2 Results

The main results are presented in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Results for the top 10 and top 20 recommendations for the SelfGNN and the baselines

From Figure 2, it is clear that the SelfGNN is able to outperform the previous recommender methods on the top 10 and top 20 recommendations.

Furthermore, they perform an ablation study on the different modules of the SelfGNN model to see what happens to the performance when different parts of the model are changed. The results are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Module ablation study of the SelfGNN model.

From the figure, we see how the performance changes when different parts of the model are either removed or changed. Notably, we see how much the performance drops when the collaborative filtering -CF is dropped.

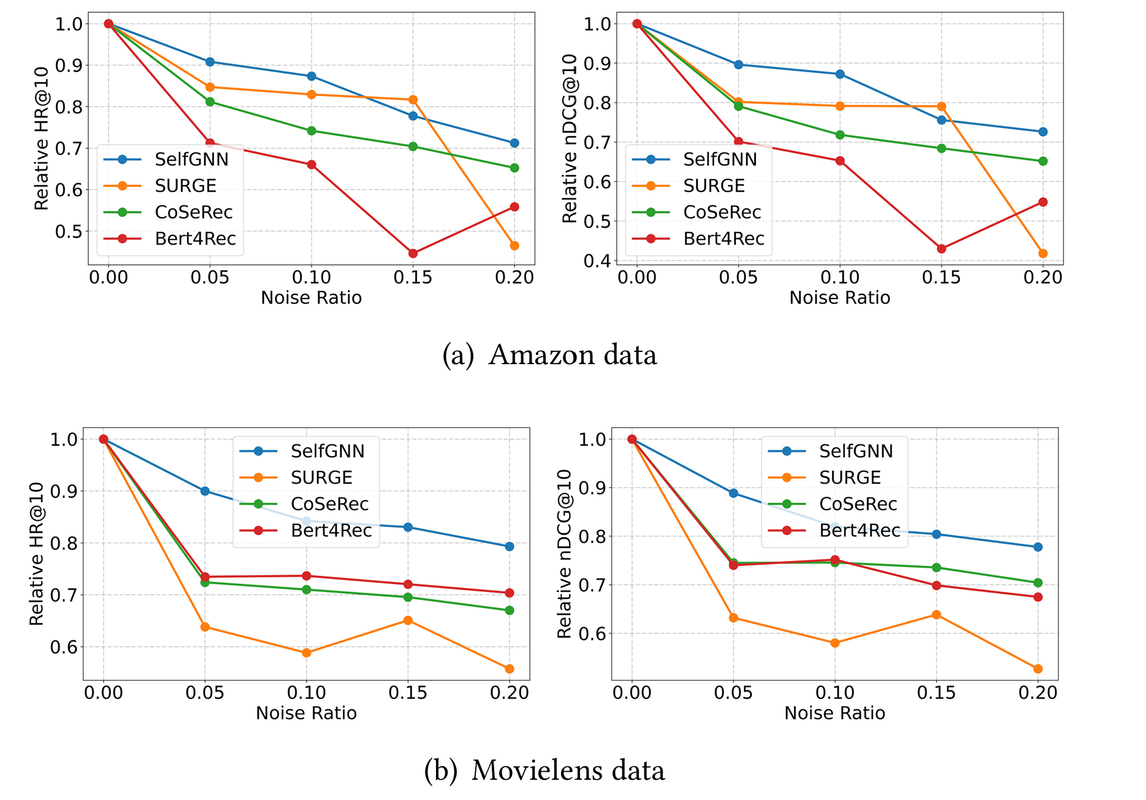

Lastly, to analyze the SelfGNN robustness against noise they conducted experiments where they randomly replaced some of the real item interactions with randomly generated fake ones. Figure 4 shows the performance of the SelfGNN and the top baselines on the Amazon and Movielens data set as the percentage of fake items increased.

Figure 4: Relative HR@10 as a function of noise ratio for the SelfGNN and top baselines on the Amazon (a) and Movielens (b) data set

From the figure, it is also clear that the performance of the SelfGNN is much more stable as more and more noise is injected into the data.

6. Conclusion

Liu et al (2024) propose a novel method to encode short and long-term user-item interactions for self-supervised learning by integrating the short-term embeddings into long-term ones. They further empirically show, that their method outperforms state-of-the-art recommender system methods in top 10 and top 20 recommendations.

Importantly, they propose to denoise the short-term information for self-supervised learning by filtering using long-term embeddings. This is quite logical, as we would expect long-term patterns to shape individual user preferences. Thus short-term instances that deviate too much from the long-term patterns can safely be assumed to be noise.

Possible direction for future research could be making the time-series continuous instead of discretized time-intervals using things such as ordinary differential equations.

Author Information

- Author name: Christian Hvilshøj

- Affiliation: KAIST School of Computing

- Research Topic: Sequential Recommendation Learning

7. Reference & Additional materials

- Main paper: Liu, Yuxi, Lianghao Xia, and Chao Huang. “SelfGNN: Self-Supervised Graph Neural Networks for Sequential Recommendation.” Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 2024.

- Github Implementation

- Reference

Vaswani, A. “Attention is all you need.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

Yingqiang Ge, Shuya Zhao, Honglu Zhou, Changhua Pei, Fei Sun, Wenwu Ou, and Yongfeng Zhang. 2020. Understanding echo chambers in e-commerce recommender systems. In SIGIR. 2261–2270.

Wei Wei, Chao Huang, Lianghao Xia, and Chuxu Zhang. 2023. Multi-modal self-supervised learning for recommendation. In WWW. 790–800.

Jinghao Zhang, Yanqiao Zhu, Qiang Liu, Shu Wu, Shuhui Wang, and Liang Wang. 2021. Mining latent structures for multimedia recommendation. In MM. 3872–3880

Mengqi Zhang, Shu Wu, Xueli Yu, Qiang Liu, and Liang Wang. 2023. Dynamic Graph Neural Networks for Sequential Recommendation. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering (TKDE) 35, 5 (2023), 4741–4753.

Jianxin Chang, Chen Gao, Yu Zheng, Yiqun Hui, Yanan Niu, Yang Song, Depeng Jin, and Yong Li. 2021. Sequential recommendation with graph neural networks. , 378–387 pages

Ruining He and Julian McAuley. 2016. Ups and Downs: Modeling the Visual Evolution of Fashion Trends with One-Class Collaborative Filtering. In WWW. 507–517

Eunjoon Cho, Seth A. Myers, and Jure Leskovec. 2011. Friendship and mobility: user movement in location-based social networks. In KDD. 1082–1090.

F. Maxwell Harper and Joseph A. Konstan. 2015. The MovieLens Datasets: History and Context. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems (TIIS) (2015).

Yehuda Koren, Robert Bell, and Chris Volinsky. 2009. Matrix Factorization Techniques for Recommender Systems. Computer 42, 8 (2009), 30–37.

Xiangnan He, Lizi Liao, Hanwang Zhang, Liqiang Nie, Xia Hu, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2017. Neural Collaborative Filtering. In WWW. 173–182.

Balázs Hidasi, Alexandros Karatzoglou, Linas Baltrunas, and Domonkos Tikk.

- Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. In ICLR

Wang-Cheng Kang and Julian McAuley. 2018. Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation. In ICDM. IEEE, 197–206.

Jiacheng Li, Yujie Wang, and Julian McAuley. 2020. Time Interval Aware SelfAttention for Sequential Recommendation. In WSDM. 322–330.

Fei Sun, Jun Liu, Jian Wu, Changhua Pei, Xiao Lin, Wenwu Ou, and Peng Jiang.

- BERT4Rec: Sequential Recommendation with Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformer. In CIKM. 1441–1450.

Xiang Wang, Xiangnan He, Meng Wang, Fuli Feng, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2019. Neural graph collaborative filtering. In SIGIR. 165–174.

More references is to be cited where \cite{} is presented but I ran out of time…