[WWW-24] AgentCF: Collaborative Learning with Autonomous Language Agents for Recommender Systems

1. Problem Definition

This paper considers the following item ranking problem:

- GIVEN: A user $u$ and a list of candidate items ${c_1, \dots, c_n}$

- FIND: A ranking over the given candidate list

- ASSUMPTIONS:

- Interaction records between users and items $\mathcal{D}={\langle u, i\rangle}$, including reviews and item meta-data, is available.

2. Motivation

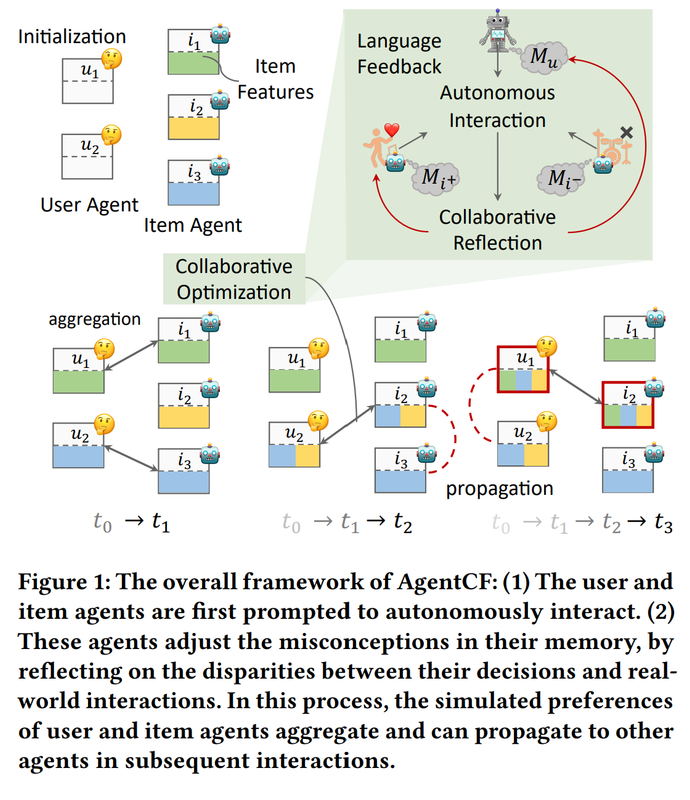

The semantic knowledge encoded in LLMs have been utilised for various tasks involving human behaviour modeling. However, for recommendation tasks, the gap between universal language modeling, which is verbal and explicit, and user preference modeling, which can be non-verbal and implicit, poses a challenge. As such, this paper proposes to bridge this gap by treating both users and items as collaborative agents to autonomously induce such implicit preference.

Existing approaches to LLM-powered recommendation that employs agents are one-sided, i.e., either item-focused or user-focused, with self-learning strategies for such agents; meanwhile, this work considers a collaborative setting where users and items do interact. From a collaborative learning perspective, this work is also novel with agent-based collaboration modeling instead of traditional function modeling (e.g., inferring embeddings of users and items for similarity measure) methods.

3. Method

An overview of the algorithm

An overview of the algorithm

3.1. Initialisation

The algorithm initialises two types of agents, users and items, equipped with memory.

- User memory includes short-term memory $M _u^s$ (natural language text describing any recently updated preference of user, initialised by general preference induced from reviews) and long-term memory $M _u^l$ (evolving records preference texts).

- Item memory includes a unified memory $M _i$ with characteristics (initialised by meta-data) of the item and preferences of users who purchased it, all in natural language.

Note that the proposed method also assumes the availability of a frozen LLM which will serve as the backbone for memory optimisation and the ranking mechanism.

3.2. Memory optimisation

The following two processes are carried out alternatively with each item along the interaction sequence of a user.

3.2.1. Autonomous Interactions for Contrastive Item Selection

From (1) the running memory of the user together with (2) a random popular item (denoted $i^-$, the negative item) and (3) a true next item (denoted $i^+$, the positive item), an LLM has to predict an item that the user will interact with, $i^o$, as well as an explanation $y _{exp}$ for such a selection. Here the two items are presented equally to the user (i.e., the ground truth is hidden).

$i^o = f_{LLM} (M _u; M _{i^-}; M _{i^+}),$ $y _{exp} = Prompt _{LLM} (i^o; M _u; M _{i^-}; M _{i^+}).$

3.2.2. Collaborative Reflection and Memory Update

After a predicted item and an explanation are obtained, they are fed to an LLM reflection module together with the user’s, positive item’s, and negative item’s memory. The information on the correctness of the prediction is available, allowing the agents’ memory to update accordingly, improving alignment between the memory and the underlying preferences.

$M _u^s \leftarrow Reflection^u (i^o; y _{exp}; M _u; M _{i^-}; M _{i^+})$ $M _i \leftarrow Reflection^i (i^o; y _{exp}; M _u; M _{i^-}; M _{i^+})$ $M _u^l \leftarrow Append (M _u^l; M _u^s)$

3.3. Candidate Item Ranking

After the optimisation process in Section 3.2. is finished, the agents are ready to be used for item ranking. Given a user $u$ and a candidate set ${c_1, \dots, c_n}$, there are three ranking strategies considered.

- Basic stategy: based on the user’s short-term memory and all item’s memory. The ranking result is $\mathcal{R} _B = f _{LLM}(M _u^s; {M _{c _1}, \dots, M _{c _ n}})$.

- Advanced strategy 1: In addition to the memory utilised in the basic strategy, we also use $M _u^r$, preference retrieved from the long-term memory by querying with candidate items’ memories. The ranking result is $\mathcal{R} _{B+R} = f _{LLM}(M _u^r; M _u^s; {M _{c _1}, \dots, M _{c _ n}})$.

- Advanced strategy 2. In addition to the memory utilised in the basic strategy, we also use memories of items that the user $u$ interacted with historically. The ranking result is $\mathcal{R} _{B+H} = f _{LLM}(M _u^s; {M _{i _1}, \dots, M _{i _ m}}; {M _{c _1}, \dots, M _{c _ n}})$.

4. Experiment

Experiment setup

-

Dataset: the authors utilised two subsets of the Amazon review dataset, “CDs and Vinyl” and “Office Products”, sampling 100 users from each of them for two scenarios, dense and sparse interactions.

- Baseline

- BPR [1]: matrix factorisation

- SASRec [2]: transformer-encoder

- Pop: simply ranking candidate items by popularity

- BM25 [3]: ranking items based on their textual similarity to items the user interacted with

- LLMRank [4]: zero-shot ranker with ChatGPT

- Evaluation Metric: NDCG@K, where K is set to 1, 5, and 10.

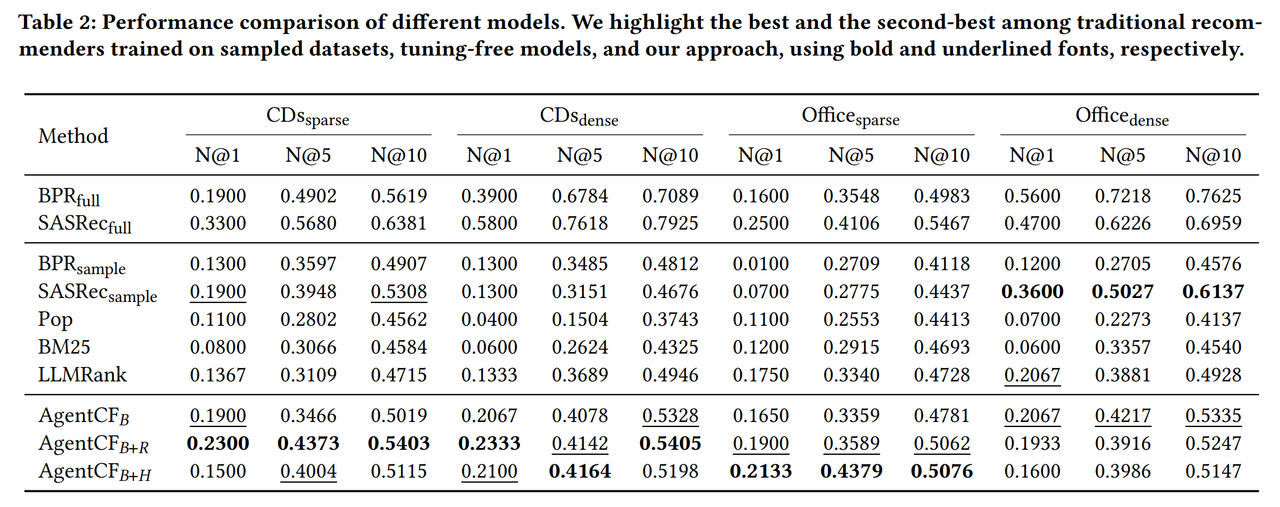

Result

Main results

The proposed method together with its three ranking strategies is comparable or outperforms baselines on the considered datasets.

Ablation

Ablation study is conducted on the inclusion of autonomous interaction, user agents, and item agents. Results show that all components are useful, except for the case of NDCG@1 on the Office category data, where the algorithm without user agent excels; this is argued by the authors to be due to the long item description text included in the data, which effectively render LLMs as sequential recommenders. Even in such a scenario, the inclusion of item agents is still shown to be necessary.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposed a novel modeling of two-sided interactions between user and item LLM agents for the recommendation ranking task, which serves as a proxy for preference modeling. This approach alleviates the gap between the semantic knowledge in general-purpose LLMs and deeper behavioural patterns inherent in user-item interactions.

I find the optimisation process of this algorithm intriguing, as it implicitly mimics the forward pass and gradient-based updates in traditional optimisation. Furthermore, the core idea of interactions between both user and item agents is indeed interesting. However, the specific implementation of it in this paper has a number of issues:

- The extensive use of the LLM backbone with very long prompts may result in instability (i.e., results may not be consistent), poor attention to all parts of the given prompts, and expensive computational costs.

- The choice of implicit contrastive learning (i.e., with negative and positive items) is presented somewhat arbitrarily. No reasoning was given as to why such contrastive learning was preferred over classifying a single item as true or false interaction, for example.

I think there can be two directions (or more) in which subsequent research can develop:

- Instead of letting agents interact superficially through an LLM prompting interface, we could either finetune models or modify embeddings that represent the agents in some way. This may potentially be less expensive than extensive prompting and at the same time provide more flexibility to agents.

- The idea of comparing product might be relevant to preference optimisation in LLM alignment (see direct preference optimisation, DPO [5]). We might be able to treat recommendation as a generative task while still optimising user or item agents with an LLM backbone.

Author Information

- Name: Quang Minh Nguyen (see me at https://ngqm.github.io/)

- Affiliation: KAIST Graduate School of Data Science

- Research topic: reasoning on language and vision data, natural language processing for social media analysis

6. Reference & Additional materials

Paper information

- Code: https://github.com/RUCAIBox/AgentCF

- Full text: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3589334.3645537

References

[1] Steffen Rendle, Christoph Freudenthaler, Zeno Gantner, and Lars Schmidt-Thieme. 2009. BPR: Bayesian Personalized Ranking from Implicit Feedback. In UAI, Jeff A. Bilmes and Andrew Y. Ng (Eds.). AUAI Press, 452–461. [2] Wang-Cheng Kang and Julian McAuley. 2018. Self-Attentive Sequential Recommendation. In ICDM. [3] Stephen E. Robertson and Hugo Zaragoza. 2009. The Probabilistic Relevance Framework: BM25 and Beyond. Found. Trends Inf. Retr. 3, 4 (2009), 333–389. [4] Yupeng Hou, Junjie Zhang, Zihan Lin, Hongyu Lu, Ruobing Xie, Julian J. McAuley, and Wayne Xin Zhao. 2023. Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Rankers for Recommender Systems. CoRR (2023). [5] Rafael Rafailov, Archit Sharma, Eric Mitchell, Stefano Ermon, Christopher D. Manning, and Chelsea Finn. 2023. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. In 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2023. . Retrieved from https://neurips.cc/virtual/2023/oral/73865